Columbus took ten Taínos to Europe at the end of his first voyage. For upcoming Indigenous Peoples’ Day, I reconstruct what the ten “discovered” during their first days after arrival, in and around Lisbon, Portugal, from March 4–10, 1493, a parallel to Columbus’s landfall on the Taíno Guanahaní (San Salvador) from October 12–14, 1492.

As depicted in Encounters Unforeseen, one of the ten Taínos was a representative of Chief Guacanagarí, dispatched to meet Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand. The remainder were captives who’d been enslaved to serve as guides and interpreters—four seized on Guanahaní on October 14, 1492, one from the many seized on Cuba in November 1492, and four from “Española’s” Samaná peninsula seized on January 15, 1493.

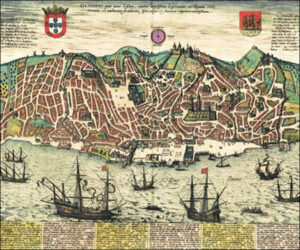

On March 4, 1493, storms forced Columbus—sailing on the Niña—to take refuge before reaching Spain in Lisbon’s harbor, shown in the first photo (with the 25th of April bridge at the mouth). Columbus had lived in Lisbon and married a Portuguese woman, Filipa Moniz Perestrelo, and he knew Portugal’s King John II, having unsuccessfully tried to convince John to sponsor the voyage. John invited him to meet in the parish of Vale do Paraíso northeast of Lisbon, and Columbus brought along two of the Guanahanían Taínos as proof of his landfall in the “Indies,” including the Taíno later baptized and known to history as Diego Colón.

The route to Vale do Paraíso took Columbus and the two Taínos through the city of Lisbon, shown in the engraving below from Civitates Orbis Terrarum (c. 1598), including past the Church of Carmo, shown in the second photo, where Columbus visited Filipa’s tomb (she’d died in 1485). Columbus’s crew and the eight other Taínos remained with the Niña while it was repaired in Lisbon’s shipyard quays.

The Taínos would have been astonished by the technological advancement of the city, particularly church and home construction and European weaponry. They would have been shocked by the animals encountered and used for transportation, labor, and food—they knew neither horse, cattle, pig, or chicken. They also would have discovered African slaves openly used in labor and penned in the large slave market near the central wharf area, and they likely feared a European intent to enslave their people.

The house in Vale do Paraíso where the royal audience occurred still exists, shown in the last photo below. King John didn’t believe Columbus had reached the Indies and asked the two Taínos separately to draw a map of their homeland with dried beans. When the two produced the roughly same map of the Taíno Caribbean, John admitted to himself that Columbus had “discovered” land previously unknown to Europeans.

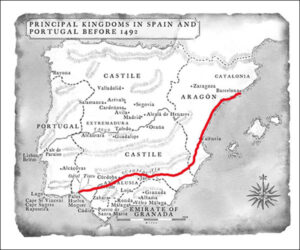

The ten Taínos would travel with Columbus through Spain for six months, two dying in Seville from European diseases, six baptized by Isabella and Ferdinand in Barcelona, one ordered to remain to live at their court, and—as depicted in Columbus and Caonabó—seven would reach Cádiz to embark with Columbus on his second voyage in September 1493, enslaved to assist in the Taíno homeland’s subjugation. Their route in Spain to meet Isabella and Ferdinand—from Palos to Barcelona—is marked in red on the map of Spain and Portugal.