Encounters Unforeseen’s protagonists are three historic Taíno chieftains—Caonabó, Guacanagarí, and Guarionex, Spain’s Queen Isabella, Columbus, and a Taíno captive Columbus seized. Portions of their life stories are sketched below.

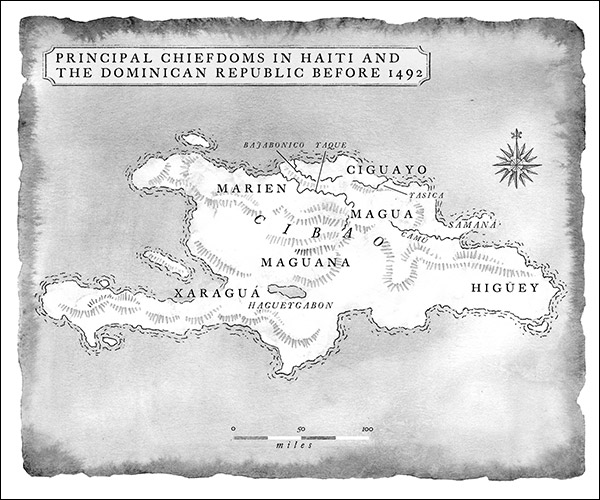

The following map, drawn for Encounters Unforeseen, shows the principal Taíno chiefdoms existing in the island of the modern Haiti and Dominican Republic before 1492:

The historical record unambiguously establishes that, when chieftain, Caonabó ruled from a village whose central batey court is known as Corral de los Indios in San Juan de la Maguana, Dominican Republic. Batey was a Taíno ballgame played by both men and women, and Caonabó’s large caney (a chief’s home) would have been on the most prominent site overlooking the court. When I took the photo below, the Corral was being used as a soccer field!

No one knows Caonabó’s birthplace. For reasons noted in Encounters Unforeseen’s Sources section, I speculated the Taíno Aniyana (Middle Caicos, Turks & Caicos). Here’s a pond on Aniyana, I suspect much like the pond in the book’s opening duck hunting scene:

Guacanagarí, Chieftain of Marien

Guacanagarí’s chiefdom was located on the northwest coast of the island, and he likely ruled from somewhere in the acreage where the Haitian town of Bord de Mer de Limonade now lies, a few miles east of Cape Haitien. It is, and was, fertile land surrounded by hillsides and mountains, including the imposing Point Picolet, the mountainous ridge that falls to the sea at Cape Haitien. The photos below are typical scenes inland and at the beach looking west toward Point Picolet.

Guacanagarí was the island’s first paramount Taíno chieftain to meet and evaluate Columbus, and the beach above is likely where they stood together on December 26, 1492. Guacanagarí had rescued Columbus when the Santa María sank the day before on reefs closer to Point Picolet. Columbus twice chose occasions at the beach to order his sailors to demonstrate the power of European weaponry to his rescuer. See Chronology, January 2, below, for second occasion.

Guarionex, Chieftain of Magua

Guarionex ruled, and presumably spent his childhood, at or near the present La Vega Vieja in the then (and now) fertile central valley of the Dominican Republic. As most people in the 15th century, he would have lived near a stream or lake for drinking water. There’s a preserved site in the Vega Vieja vicinity near a stream, which is typical of where his home might have been, as shown in the photos below.

Guarionex and Caonabó didn’t meet Columbus during Columbus’s first voyage, but during the second, after Columbus had commenced the Taíno homeland’s brutal subjugation and enslavement. The meetings between Guarionex and Columbus likely would have occurred in the floodplain below the site pictured above, where the rivers Yaque and Camú flow (both rivers have their original Taíno names). It’s ultimately through Guarionex that we know about the Taíno religion as practiced in the 15th century, as he and his subjects imparted information about Taíno spirits and worship to a friar Columbus instructed to study and record (undoubtedly imperfectly) the Taíno religion. See Chronology, Late May or Early June.

Spain’s Queen Isabella

Born in 1451, Isabella grew up in the small, northern Castilian town of Arévalo. She likely worshipped sometimes in its Church of St. Michael, which had been converted from a mosque during the Reconquista, the Christian reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula from the Islamic rulers who had invaded in the 8th century. The church is modest and at the town’s edge, serenely overlooking the river ravine that served as Arévalo’s western defense. The photos below show the church’s altarpiece and pews for royalty and nobility, where Isabella would have sat with her mother, younger brother Alfonso, and grandmother.

The next three photos chronicle Isabella’s adolescence and ascent to the Castilian throne: the city of Segovia, viewed from atop its alcazar, where Isabella was held under guard when a teenager by her older brother, King Enrique IV; the street in Cardeñosa where Alfonso died in 1468 and Isabella first contemplated seeking the throne herself, regardless of living in a male-dominated society; and the church doorstep in Segovia’s central square where she crowned herself in 1474 after Enrique’s death.

Key to her ascent to the throne, Isabella married Ferdinand in 1469. The marriage ultimately united the separate kingdoms of Isabella’s Castile and Ferdinand’s smaller Aragon.

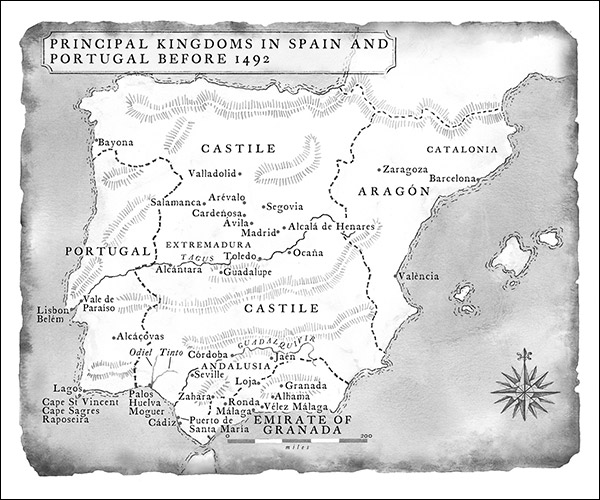

Prior to Columbus’s voyage, Isabella and Ferdinand took various actions for which they would become known to history as the Catholic Monarchs: they established the Spanish Inquisition, waged war to complete the Reconquista by conquering the Islamic kingdom of Granada in southern Spain, and expelled the Jews from Spain—all to Christianize their kingdoms.

They also began to seek a Spanish colonial empire. There were Castilian settlements on three of the smaller Canary Islands, and, in the early 1480s, they brutally subjugated and Christianized the indigenous peoples living on the largest island, Gran Canaria.

Columbus

Likely also born in 1451, Columbus spent his childhood and adolescence in Genoa and neighboring Savona. There is a restored “Columbus House” in Genoa shown below. It’s uncertain whether this house is the one Columbus grew up in, but it’s in the immediate area indicated for his parents’ home by preserved notarial deeds.

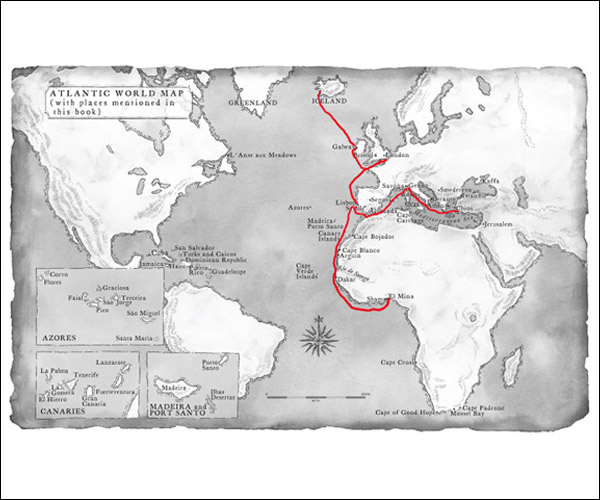

Columbus matured as a young man sailing the Mediterranean and the coasts of Europe and west Africa.

While historians debate Columbus’s pre-1492 sailing experiences, he likely participated on a voyage to Chios (the Greek island) to secure supplies of mastic (then used for medicinal purposes) when about twenty years old. At the time, Chios was a Genoese trading colony and a key source of slaves for Genoese merchants’ slave trading. The photo below is of Chios’s southern region where mastic trees were (and are) grown.

He also may have sailed—when in his mid-twenties—from England to Iceland on a trading expedition for whale and fish oil, the ships restocking en route at Galway, western Ireland. The next photo is of St. Nicholas Collegiate Church in Galway, where locals tell visitors that Columbus prayed.

In about 1479, Columbus married advantageously into a Portuguese family of minor nobility and then went to live in family possessions on the Portuguese Atlantic island of Porto Santo—which then served as a restocking station for African slave and gold traders. The photo below shows this island’s rugged western cliffs, where Columbus is said to have inspected driftwood blown east—wondering what lay west.

In his thirties, Columbus sailed to the Portuguese slave and gold trading post at El Mina (modern Ghana). The following photo is of the fort and slave dungeons now preserved at Mina, larger than during Columbus’s day.

Columbus’s views on conquest and enslavement reflected his upbringing and experiences and were typical of many contemporary European Christians.

Columbus first proposed his voyage in person to Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand on January 20, 1486, in Alcalá de Henares (near Madrid). The next photo shows the preserved entranceway to the building where the audience occurred.

Isabella and Ferdinand reluctantly agreed to sponsor the voyage—which they thought fanciful—only after completing Granada’s conquest in January 1492. They met Columbus to finalize arrangements for the voyage in the City of Granada’s famous Alhambra, shown below.

As related in the Chronology below, Columbus seized Taíno captives as he explored the Caribbean. In 1493, he took nine of them and a representative of Chief Guacanagarí back to Spain, where they spent six months.

Columbus’s Journal doesn’t individually name or identify the captives seized, but the subsequent historical record shows Columbus had a long-standing use and trust for one of the younger ones seized on the Taíno island Guanahaní (possibly the modern San Salvador) on October 14, 1492. This captive’s life can be traced individually commencing in 1493 and for years thereafter, and it’s through his eyes that Encounters Unforeseen portrays the Taíno “discovery” of Europe.

This captive’s role in translating conversations between Taínos and Europeans during the encounters must have grown substantially as Columbus’s voyage progressed through the Caribbean. I suspect it was this captive who: accompanied Columbus’s men inland on Cuba in November 1492 (Chronology, November 2); helped translate conversations between Columbus and Chief Guacanagarí (Chronology, December 26); and met Portugal’s King John II (Chronology, March 10).