As depicted in Columbus and Caonabó, in December 1493 fierce easterly trade winds and harsh winter storms severely impeded Columbus’s journey east to select a permanent site to initiate the island’s conquest. When he finally anchored in the inlet at Río de Gracia, Columbus concluded its river was too meager. Then a violent storm prevented him from reaching Monte Plata. After three weeks—with provisions dampening and rotting, livestock sickening, and the voyagers’ grit, patience, and faith wasting—Columbus felt compelled to end the search.

He had found a river-mouth cove sheltered from wind by a promontory where the coastline jutted north between Monte Christi and Río de Gracia, and he decided to establish his base there. The river (the Bajabonico, which retains its Taíno name today) was fulsome, and the promontory was higher, defensible ground situated within fifteen minutes’ walk, bordered by a beach and tidal lagoon at its northern end, the sea to the west, and the river’s ravine to the south. The promontory’s eastern flank was pregnable to attack but forested, and “Indians” weren’t resident on it. A lengthy wall of stone—astonishingly perfect for a quarry—flanked the riverbed close to the promontory, and a verdant floodplain suitable for farming and grazing livestock extended southwest for miles.

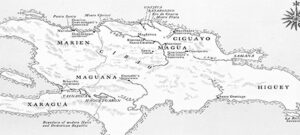

On New Year’s Day 1494, 528 years ago, the fleet anchored in the cove and debarked, fourteen weeks after departing Cádiz. Although Columbus didn’t appreciate it yet, the area was a hinterland outside the territories of the island’s principal Taíno chiefdoms. As shown on the map below (contained in Columbus and Caonabó), Chief Guacanagarí’s Marien lay to the west, Chief Mayobanex’s Ciguayo lay to the east, and Chief Guarionex’s Magua lay to the south. Chief Caonabó’s Maguana was distant. Fortuitously for Columbus, usurpation of the site (La Isabela, in the modern Dominican Republic) didn’t encroach on either Caonabó’s or other principal chieftains’ direct sovereignty.

The photos below are: the cove, taken from the site of the historic mouth of the Bajabonico looking east to the promontory and the remains of Columbus’s fortified residence; the Bajabonico itself, on the flood plain; Columbus’s residence; the promontory, looking north from the residence; and the promontory’s northern rim, looking south to it from the northern beach.