After dispatching reinforcements to Fort Santo Tomás, Columbus decided on the next steps to his conquest of “Española.” Alonso de Hojeda would replace Pedro Margarite as the fort’s warden, and Margarite was to march about the island with a squadron of almost four hundred men to capture Chief Caonabó, survey the island’s riches, establish Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand’s sovereignty, and cow the Indians to obedience. Tall crosses were to be erected throughout the island to mark it as Christian. While traveling to the fort, Hojeda also was to punish those Indians guilty for stealing Christians’ clothing at the Yaque River crossing site.

Caonabó’s decision whether to attack Fort Santo Tomás was both military and political. He then was one of the island’s six principal chieftains (as indicated on the map posted January 1), and the fort lay within territory under the rule of Magua’s Chief Guarionex, Caonabó’s peer. Caonabó had advised Taínos living near the fort to not supply it food, but dispatching his own warriors to attack the fort appropriately required Guarionex’s participation, approval, or acquiescence, as well as consensus of other principal chieftains. At this time, Caonabó redoubled efforts to establish an alliance to expel the Europeans from the island, rather than attacking unilaterally.

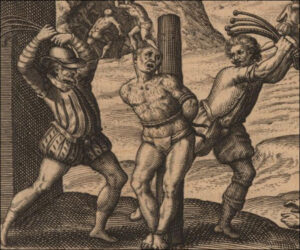

As depicted in Columbus and Caonabó, on April 9, 1494 (528 years ago), Hojeda departed Isabela with Margarite’s squadron, including sixteen mounted horsemen and over three hundred bearing crossbows and firearms. At the Yaque, he seized two Taíno youths and publicly mutilated them by slashing off their ears, purportedly as punishment for the previous theft of clothing. Days later, Columbus announced he would behead the youths’ chieftain and others for their complicity in or failure to punish the theft, but he commuted the beheadings following pleas for mercy, satisfied other chieftains had been warned of his expectations for obedient submission.

Taíno chieftains throughout the island saw these events as unambiguously confirming Caonabó’s warnings that the Europeans were an enemy, and many warily began to embrace the alliance he sought.

The following photo is of the Yaque near its juncture with the Mao, at a spot I envision resembling the fording site for Spaniards traveling between Isabela and Fort Santo Tomás. The image (included in Columbus and Caonabó) is of the punishment of a villager, taken from Theodor de Bry, 1598, courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library.