Prior to the second voyage, Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand had instructed Columbus promptly to explore the land the “Indians” called “Cuba” to ascertain whether it was the Indies mainland, and he’d advised them that this exploration would follow establishment of “Española’s” “gold mines.” But, by April 1494, gold’s collection on Española remained meager, and Columbus was keen to show his sovereigns fresh victories by locating the wealthy Asian civilizations he’d promised to reach.

On April 24, 1494 (528 years ago), he sailed west from Isabela for Cuba, whose northeastern coast he’d explored on his first voyage. The fleet consisted of three nimble caravels—the Niña of the first voyage serving as flagship, with a crew of almost thirty, and two smaller vessels, with fifteen men each. Soldiers and scribes were enrolled, and an attack dog was included with the weaponry. However, most of the men were salted sailors, including Juan de la Cosa (who would draw the famous world map of 1500), and ship artisans, who could caulk and repair. Columbus’s principal enslaved Taíno guide/interpreter—seized on the Taíno Guanahaní (San Salvador) on the first voyage and generally known to history by his baptized name “Diego Colón”—served on the Niña.

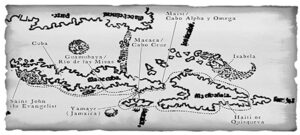

The map below (contained in Columbus and Caonabó) is a portion of Peter Martyr d’Anghera’s map of New World, 1511 (courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library), with the route of Columbus’s five-month Cuban and Jamaican exploration marked thereon. I also repost the photo of the reconstruction of the Niña berthed in the Wharf of the Caravels Museum, Palos, Spain.

Columbus established a five-member ruling council to govern the settlement in his absence, including Fray Buil (the papal nuncio). Regardless, as depicted in Columbus and Caonabó, Columbus’s working relationships with both Pedro Margarite (who was responsible for capturing Chief Caonabó) and Fray Buil had sorely deteriorated by the time of his departure—irreparably so, to be discussed in future posts.