As depicted in Columbus and Caonabó, a third of the voyagers—some four hundred men—were beset with fevers, headaches, vomiting, and diarrhea within days of debarking on the promontory. Modern epidemiologists speculate that the causes included dysentery from the voyagers’ first-time exposure to Caribbean bacteria and parasites, as well as influenza borne by the fleet’s pigs. Nevertheless, wood and thatch huts for a new town quickly dotted the site, including makeshift structures for Columbus’s residence and the town’s church, both to be constructed permanently with stone, packed earth, and tiles.

The surrounding territory wasn’t densely populated, but there were small Taíno villages nearby, and Columbus promptly strove to establish peaceful relations with the local chieftains—the fate of the Navidad garrison haunting him. The sight of seventeen large ships of unknown construction, twelve-hundred armed pale-skinned intruders, and hundreds of beasts never seen before was imposing, and concord came readily, as the local chieftains feared a confrontation. Columbus traded with the chieftains for food in return for items novel to them, including hawks’ bells and gloves.

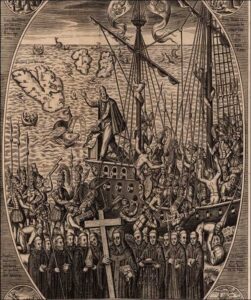

On January 6, 1494, 528 years ago, Columbus summoned the voyagers to celebrate the Feast of Epiphany before the church, and Fray Bernardo Buil—the leader appointed by Pope Alexander VI for the dozen missionaries—presided over the settlement’s first mass. Columbus named the town for the queen, La Isabela.

The photos below are of the remaining footprints of the walls of Columbus’s residence and the church. The illustration (contained in Columbus and Caonabó) is a seventeenth century European conception of Columbus’s arrival at Isabela (taken from Honorius Philoponus, 1621, courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library, Providence, Rhode Island).

A graveyard can be seen beyond the church, where voyagers who succumbed to disease were buried.